What Is a Software-Defined Vehicle?

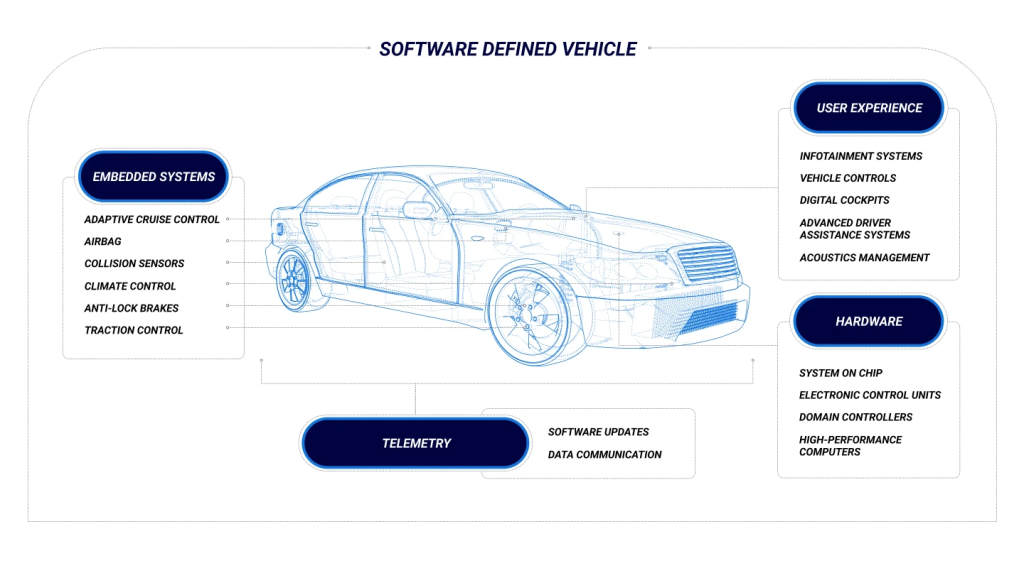

A Software-Defined Vehicle is any vehicle that manages its operations, adds functionality, and enables new features primarily or entirely through software.

it reflects the gradual transformation of automobiles from highly electromechanical terminals to intelligent, expandable mobile electronic terminals that can be continuously upgraded.

To become such intelligent terminals, vehicles are pre-embedded with advanced hardware before standard operating procedures (SOP)—the functions and value of the hardware will be gradually activated and enhanced via the OTA systems throughout the life cycle.

Driving Forces of Software-Defined Vehicles

In the past, the automotive industry stood as a testament to the power of combustion engines and the prestige of owning a car with the “most exhaust pipes.” Today, this old-school paradigm is under‐going a seismic transformation. Four major innovations—electrification, automation, shared mobility, and connected mobility—are happening all at once, leading to dramatic changes in the auto mobile landscape.

Firstly, industry development requirements: software & algorithm— indispensable for the development of connected, autonomous, shared, and electrified automotive technologies.

Secondly, consumers expect similar behaviors and experience from vehicles as with smartphones. Many are left wondering: why can’t my $50,000 car perform the same tasks as my $300 smartphone?

From this frustration emerged the idea of a software-defined vehicle (SDV), a car that’s fully programmable. New features can be developed and deployed within a matter of months, not years, and there’s extra computational capacity for future updates that can be delivered wirelessly.

Goal’s of SDV

it’s about the customer experiences we build. And these customer experiences cannot aim simply to rebuild the smartphone experience.

This is about creating a “habitat on wheels” powered by cross-domain applications and data fusion

Habitat on Wheels

During the past decade, many car manufacturers have sought to replicate successful smartphone applications in their cars. In many cases, however, these in-vehicle applications could not match the quality of the smartphone apps. In addition, consumers usually don’t want redundant experiences, inconsistencies between their digital ecosystems, or the irritation of cumbersome data synchronization.

SDV surpass the concept of a “smartphone on wheels.” Instead, it has to enable a “habitat on wheels,” utilizing the specifics of the car to provide multisensory experiences that a smartphone could never match. With multiple displays and a network of hundreds of sensors and actuators, the SDV brings together domains like infotainment, autonomous driving, intelligent body, cabin and comfort, energy, and connected car services,

Passengers feel recognized as they enter a vehicle personalized to their needs, one that is a clear departure from the impersonal con‐ fines of traditional cars.

SDVs have revolutionized our perception of mobility. It’s no longer merely about getting from point A to point B but about making the journey itself enriching. Thanks to advanced driver-assistance systems and autonomous driving, we’re embracing the transformative, multisensory power of the SDV.

Benefits of Software-Defined Vehicles

The benefits of Software-Defined Vehicles include:

- Improved safety via features such as anti-collision systems and driver assistance

- Increased comfort through onboard infotainment systems that integrate connected features such as music and video streaming

- Deeper insights into vehicle performance through telematics and diagnostics, allowing for more effective preventative maintenance

- The capacity for automotive manufacturers to add new features and functionality with over-the-air updates

- Increased value of the vehicle over time as new features are added via software updates

- Connectivity between vehicle and smartphone, allowing drivers and passengers to interact with their cars in new ways

- Continuous connectivity, delivering real-time information services to and from the vehicle

Cross-Domain Applications and Data Fusion

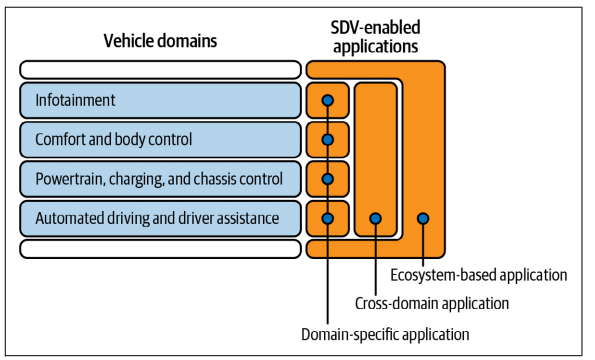

Today, vehicle experiences often occur in isolated domains. But the future with SDVs promises to blur the boundary between the vehicle and the outside world. Experiences will be cross-domain, where various vehicle functions and systems intercommunicate and interact harmoniously to enrich the overall journey.

Consider the example of a digital “dog mode” that some cars already feature. The vehicle monitors your dog in the car while you are out shopping. Because it is hard for dogs to cool down, a hot car interior on a summer’s day is often enough to cause serious injuries

or even death. This is a perfect illustration of customer-centric and cross-domain functionality. It involves multiple systems: the car’s air conditioning to maintain a comfortable temperature, the infotainment screen to display a message letting passers-by know not to worry as the dog is safe and comfy, and the battery management

system to ensure the car has sufficient energy. All these domains are coordinated in order to ensure the dog’s safety and comfort.

In this connected ecosystem, your car could even become a creative extension of your social media presence. With your permission, it could capture a stunning sunset through its high-quality on-board cameras during a scenic drive and propose a pre-edited post for your approval.

Cross-domain experiences also extend to personal wellness. Imagine that your fitness wearable signals that you’ve had an intense work‐ out. In response, your car sets the cabin temperature to a cooler setting, selects soothing illumination for the ambient lighting, and plays your favorite cool-down playlist. By seamlessly integrating with your digital devices, your car enhances your post-workout recovery and comfort.

Impediments: Why Is Automotive Software Development Different?

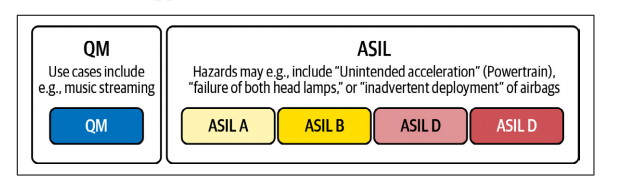

ISO 26262. This standard deals with the functional safety of electrical and electronic systems within vehicles and is fundamental to the concept of an SDV.

To quantify the risk, the standard employs a framework known as Automotive Safety Integrity Levels (ASIL), illustrated in Figure 1-3, which classifies hazardous events that could result from a malfunction based on their level of severity, exposure, and controllability. Levels of risk range from ASIL A, the lowest level, to ASIL D, the highest level. ISO 26262 defines the requirements and safety measures to be applied at each ASIL.

The SDV is more than a simple mobile device; it’s a sophisticated ensemble of systems

that prioritizes safety as much as functionality and convenience.

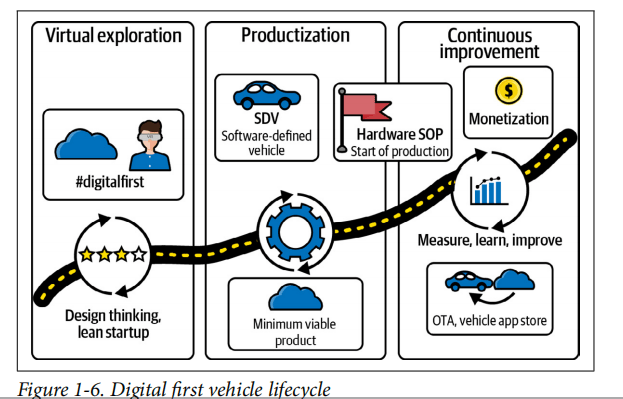

Rethinking the Vehicle Lifecycle: Digital First

Historically, the lifecycle of a vehicle was defined by the simultaneous production and deployment of tightly coupled hardware and software. Once the vehicle was in the consumer’s hands, its features remained essentially unaltered until its end of life. However, an SDV paradigm allows for the decoupling of hardware and software release dates—a prerequisite for a digital first approach, which puts design and virtual validation of the digital vehicle experience at the start of the lifecycle.

Software-Defined Vehicle Architecture

A Software-Defined Vehicle’s software and hardware architecture tend to be incredibly complex, often comprising multiple interconnected software platforms distributed across as many as one hundred electronic control units (ECUs). Some manufacturers are attempting to rationalize this down to fewer ECUs controlled by a very powerful central computer—but either way the architecture of Software-Defined Vehicles can be broken down into four distinctive layers:

1. User Applications

User applications are software and services that interact or interface directly with drivers and passengers. These may include infotainment systems, vehicle controls, digital cockpits, etc.

2. Instrumentation

Systems at the instrumentation layer are generally related to a vehicle’s functionality but don’t typically require direct intervention from a driver. Examples include Advanced Driver Assistance Systems (ADAS) and complex controllers.

3. Embedded OS

The core of the Software-Defined Vehicle, the embedded OS manages everything from sandboxing critical functions to facilitating general operations. These are typically built on microkernel architecture, allowing software capabilities and functionality to be added or removed modularly.

4. Hardware

The hardware layer includes the engine control unit and the chip on which the embedded operating system is installed. All other physical components of the vehicle also fall under this category, including cameras and other vehicle sensors.

Learning from the Smartphone Folks: Standardization, Hardware Abstraction, and App Stores

Today, almost every car model, even those from a single manufacturer, employs custom hardware and software components sourced from various suppliers. The result: extreme fragmentation combined with monolithic programming frameworks, where creating a “vehicle app” that can run across multiple models of the same manufacturer seems nearly impossible. blueprint for overcoming this fragmentation. Its solution was multipronged

A set of standardized vehicle APIs would greatly simplify the process of creating software for vehicles. By ensuring that these APIs have minimal fragmentation, developers could write software once and have it work across multiple vehicle models.

Hardware abstraction layer (HAL). This acts as a bridge between the software applications and the multitude of vehicle hardware variations. It ensures that software can run irrespective of the underlying hardware differences, adding a layer of consistency and predictability.

Supportive software stack (vehicle OS)

A robust software stack that’s in harmony with the standardized APIs and HAL ensures

that software can interact seamlessly with a vehicle’s components, making software-driven innovations easier to introduce and adopt

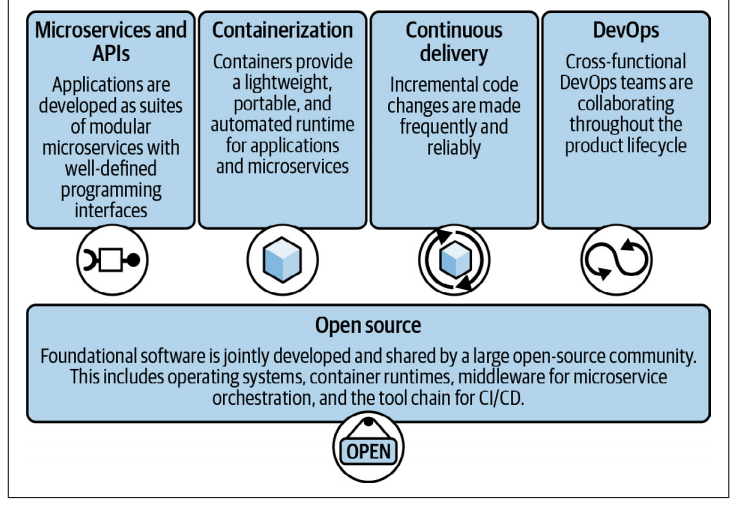

Vehicle OS and Enabling Technologies

We will start by looking at emerging electrical and electronic (E/E) architecture Key elements of E/E and SOA are hardware abstraction, vehicle APIs, and the SDV

tech stack. Modern vehicles use OTA updates to support post-SOP updates,

we assess the SDV specifically from the perspective of the E/E architecture. We identify the influence of the SDV paradigm on the different functional domains and determine the relevant drivers that must be considered when changing existing solutions. Tapping into our experience as a comprehensive solution provider, we explore how existing archi tecture components such as control units, sensors, actuators, and the wiring harness

need to be modernized or replaced and where new solutions need to be added

What is E/E architecture?

In the term “E/E architecture”, E/E stands for “electrical/electronic”, and architecture means “configuration, design concept, and design method”. Combined, E/E architecture is defined as the system that connects in-vehicle ECUs, sensors, actuators, etc.

In recent years, automobiles have evolved rapidly, and they continue to be equipped with new functions, such as driver assistance and automated driving, and functions for connectivity, personalization, and infotainment.

Due to the need for processing that is tailored to each purpose, the number of ECUs installed in automobiles has exceeded one hundred. Innovations in E/E architecture are beginning to be introduced, in order to develop software that simplifies the connection of these increasingly complex ECUs and keeps them in optimal condition.

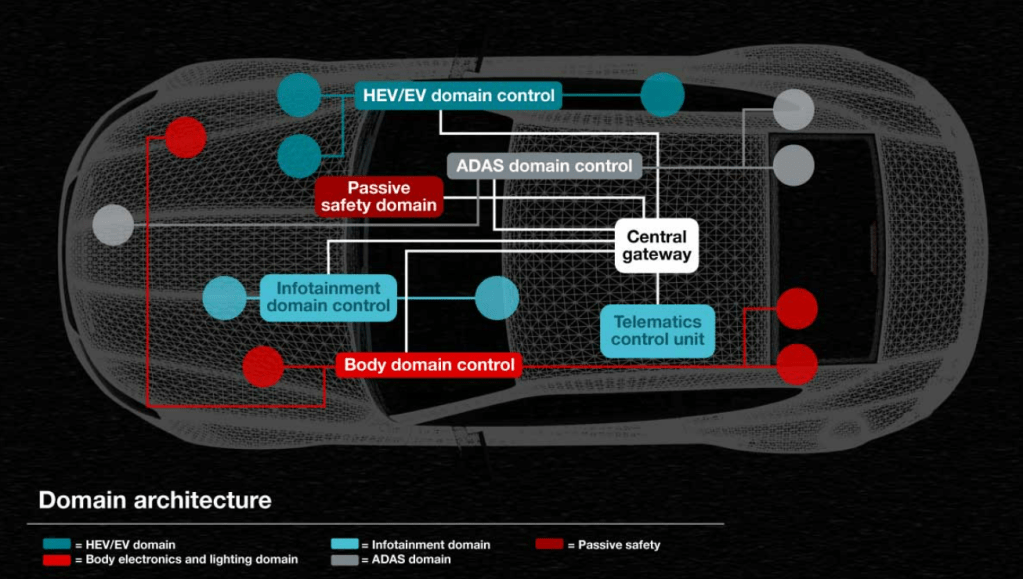

A brief explanation of domain architecture

Domain architecture classifies ECUs into domains based on their functionality. In contrast, zonal architecture is a new approach that categorizes ECUs based on their physical location within the vehicle and leverages a centralized gateway to manage communication. This physical proximity reduces cabling between ECUs, saving space and reducing vehicle weight, while also improving processor speed.

To understand domain architecture, start with the idea that ECUs are generally divided into five types based on functionality, as shown in Table 1.

| Domain | ECU functions |

| Powertrain domain | Manage vehicle driving functions, including electronic motor control, battery management, engine control, transmission and steering control |

| Advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS) domain | Processes information from a variety of sensors, including camera modules, radar modules, ultrasound modules, and sensor fusion, and makes decisions to assist the driver |

| Infotainment domain | Manages in-car entertainment and exchanges information between the car and the outside world, including the head unit, digital cockpit, and telematics control module |

| Body Electronics/Writing Domain | Manages interior comfort, convenience, and lighting functions, including body control modules, door modules, and headlight control modules |

| Passive safety domain | Controls safety-related functions such as airbag control module, brake control module, and chassis control module |

Various ECUs communicate and exchange data via the network. The network is unique and appropriate within each domain, and at the same time communicates with ECUs belonging to external domains. Gateways act as bridges to accommodate the fact that networks in one domain can be different from networks in other domains.

Figure 1 shows a car with a domain-based architecture. In this diagram, one centralized gateway module is connected to various domains within the vehicle. Each domain performs multiple functions. A domain controller, for example a control unit in a car that is responsible for the powertrain, has gateway functionality. This domain gateway supports data communication between the multiple ECUs that make up the domain, and from the domain to other domains within the vehicle.

Zone architecture overview

If we assume that the car is a room and the ECU is a group of people gathered in that room to discuss various topics, then the domain architecture arranges those participants in a chaotic manner. It will be. As a result, each participant must shout loudly (using long cable runs and commensurate power) to be heard by other participants in the conversation group spread across the room.

The car shown in Figure 2 uses a zonal architecture to organize ECUs and add on-board computing modules based on their location in the car. This in-vehicle computing module is a computer with high processing power that can perform all calculations regardless of function. The diagram also shows multiple zone modules and multiple edge nodes associated with each. These exist in different areas of the car.

It is also possible to use a low-bandwidth network, such as a controller area network (CAN), to communicate between the various zone modules and a centralized gateway or computing module. However, a high-speed network like Ethernet is also a good choice. This is because they can provide highly reliable and smooth operation over a wide automotive temperature range. PCIe is a good choice for networks to implement distributed computing between centralized computing modules and zoned modules.

Advantages of zone architecture for power distribution

Engineers can also take advantage of this technique of ECU reorganization to optimize power distribution architectures. In particular, it will be possible to redesign the smart junction box that distributes power to the various loads and ECUs in the car. Specifically, relays and fuses can be replaced with semiconductor solutions.

In a zoned architecture, multiple power distribution boxes are distributed so that each power distribution box can power the modules within its zone. Figure 2 shows the concept of power distribution in a zoned architecture. From this diagram, you can see that each zone’s power distribution function also integrates a zone module that manages network traffic. This new power distribution architecture reduces harness and cable weight. The result is improved fuel efficiency for cars with conventional internal combustion engines, and longer range for electric cars with batteries.